The Angel of Curacao

How Dutch consul Jan Zwartendijk saved thousands of Jews

Photos: Boys Town Jerusalem and Zwartendijk Family Archive

When Jan Zwartendijk heard the telephone ring in his office, he hesitated. It was almost six o’clock in the evening. He was already outside, ready to go home to his wife Erna and their three children. The treelined Laisves Aleja, Kovno’s widest boulevard, beckoned.

The telephone was still ringing.

He knew it couldn’t be a customer. Not on that day: May 29, 1940. Everyone in Kovno, then Lithuania’s capital, was too busy. They were either anxiously awaiting the arrival of the dreaded Soviet army or savoring the last few hours of Lithuania’s freedom.

Nor could it be his boss at Philips’s headquarters back in the Netherlands. International phone calls were too expensive even for one of the world’s largest manufacturers of radios and other electrical equipment.

The telephone was still ringing. Who was calling?

Zwartendijk reentered his office — and at that moment, the 43-year-old businessman from Holland entered Jewish history. For in just a few short months, “Mr. Radio Philips,” as Zwartendijk was known in Kovno, would be the catalyst for saving more than 2,000 Jewish lives, including the entire Mir Yeshivah, and receive a new moniker: the Angel of Curaçao.

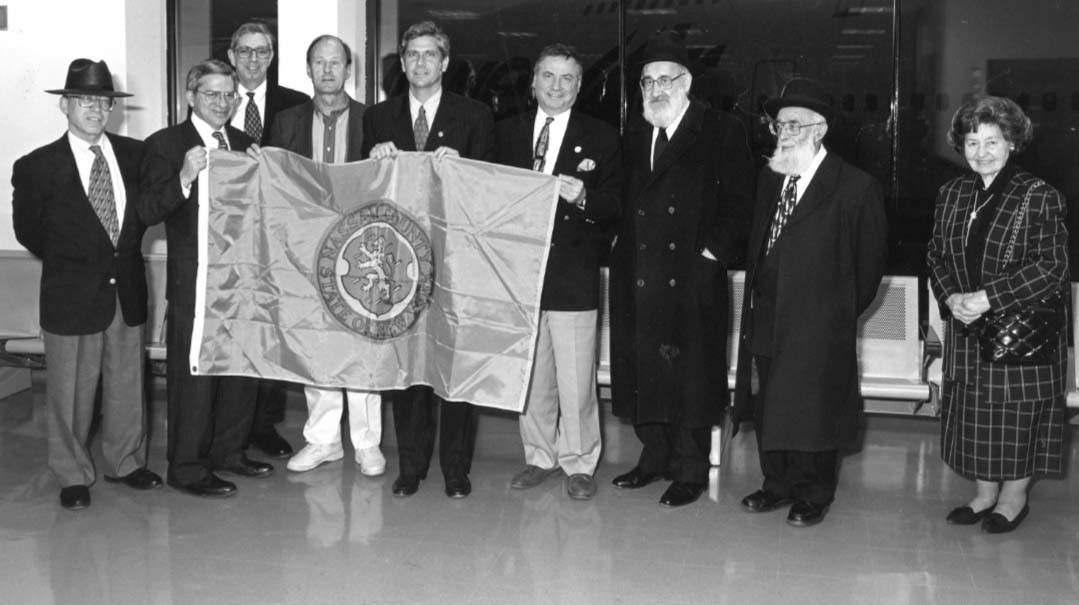

Jan Zwartenkijk never knew if the thousands of Curacao visas he issued actually helped anyone survive, but his children learned the answer: Their father had saved over 2,000 Jews. Jan Zwartendijk Jr. enroute to Israel from New York with a grateful group of survivors

Calling Mr. Radio Philips

In September 1939, the Germans overran western Poland, while the Soviets occupied the eastern half. More than 10,000 Polish Jewish refugees fled to Lithuania, which at the time was a neutral country. (It would be occupied by the Soviets in June 1940 and then by the Germans a year later.) Among the refugees from Poland were thousands of rabbanim and yeshivah bochurim.

The Germans also invaded their neighbor to the west, the Netherlands, and occupied that country in May 1940. But Dutch queen Wilhelmina and the government didn’t resign; they went into exile in England. From there they still ruled over their territories in the East Indies, as well as in the Caribbean: Suriname, a small country on the northeastern coast of South America, and several islands in the West Indies, including Curaçao. And they still had envoys and consulates in many countries.

Ambassador L. P. J. de Decker was one of those envoys. Stationed in Riga, Latvia, his territory also included Estonia and Lithuania. It was the latter country that was giving him a headache. The Dutch consul stationed in Kovno, Herbert Tillmanns, whose wife was a suspected Nazi sympathizer, had resigned rather than be fired. De Decker needed to find a temporary replacement. He picked up the phone and dialed the number of the Philips manager in Kovno.

When he heard de Decker’s request, Jan Zwartendijk protested that he was a businessman, not a diplomat. That was fine, de Decker assured him. Envoys were diplomats. Consuls, who were on a lower rung in the diplomatic hierarchy, just had to renew a few passports and help Dutch citizens in other small ways.

Zwartendijk correctly guessed that in wartime, even a consul would have more serious, and possibly dangerous, work to do. But when he continued to protest, de Decker played his trump card: The Netherlands needed a loyal representative in Lithuania. Those who opposed Nazism and Communism couldn’t hide their heads in the sand and do nothing. Besides, de Decker assured Zwartendijk, he would give the new consul any help he needed.

Jan Zwartendijk accepted the job. He also agreed to house the consulate, which didn’t have a permanent home, in his office. He had to get permission from Philips for both, but he and de Decker knew that wouldn’t be a problem.

Until 1939, the CEO of the company was Anton Philips, who was descended from Jews who left Germany in the mid-1800s. Worried not only about the possibility of war, but also Germany’s virulent anti-Jewish sentiment, Anton Philips began transferring the company’s Jewish senior managers to safety in the Americas in the early 1930s. He also tried to keep the company free from Nazi sympathizers. Anton’s successor, Frits J. Philips, would continue to try to protect his Jewish employees even after the Germans occupied Holland. And when the Nazis tried to force the company to help with the German war effort, Frits Philips — who would later be named one of the Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem — did what he could to sabotage production.

Although Zwartendijk’s official appointment would only come a few weeks later, he unofficially became the new Dutch consul that evening. After he picked up the consular stamps and some official documents from Tillmanns, he was in business.

Oops! We could not locate your form.