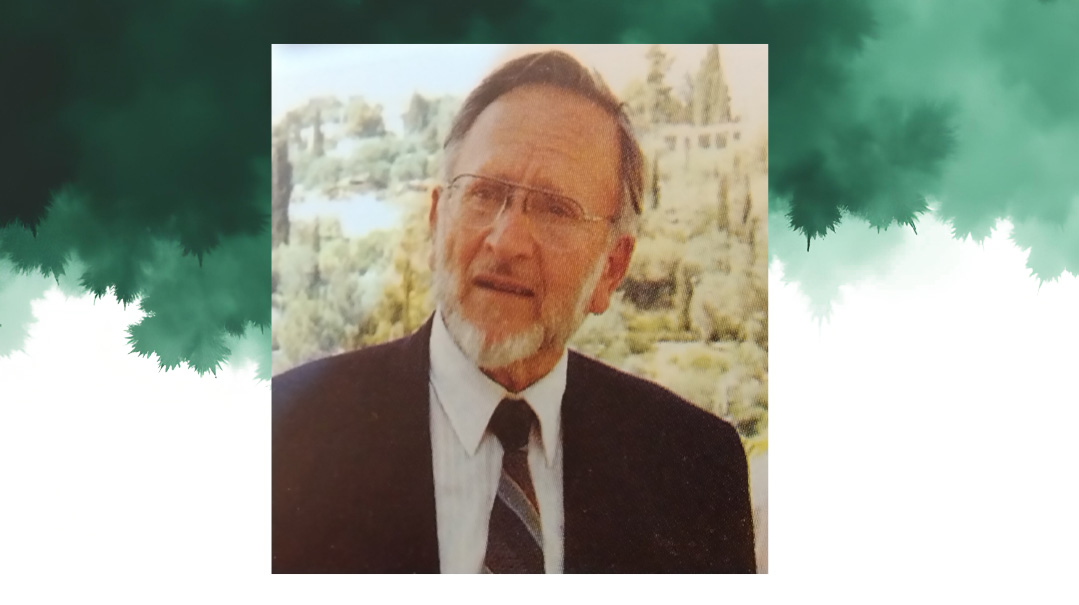

All About Love

Rabbi Dovid Trenk used love to reach and teach

Writing a book is always a journey, but sometimes, there are two journeys taking place at once.

You learn about your subject, and you learn about yourself.

Like most of my other books, this one grew out of a magazine tribute, but that was no easy feat either. Rav Dovid Trenk was niftar on a Sunday, which in magazine terms, is the eleventh hour. If we were going to cover it that week, the article would have to be written within hours. And while it’s never simple to speak to those closest to a niftar, after a few days, at least they have some clarity, the ability to express themselves. But now, when the pain was still so fresh and searing?

There’s such a thing as too soon.

Still, this was Rabbi Trenk. Just saying his name caused people to smile, for he was a man who’d spent the better part of his life teaching people not to say “I can’t,” to live big and be big — and so we had to try.

For the talmidim of Rabbi Dovid Trenk, there would never be another like him. There was an army out there who deserved to have the world know who their rebbi was.

So we started late on Sunday afternoon and submitted it just ahead of the deadline at Monday dawn and, baruch Hashem, we’re still writing the story.

What I learned, first off, is that the talmidim of Reb Dovid aren’t just the formal alumni of the respected yeshivos, Adelphia and Moreshes Yehoshua, in which he taught. They were behind the counters of pizza shops, yungeleit from the vasikin minyan at which he davened every morning, and yes, even gedolim.

As one prominent rosh yeshivah conceded to me, “Reb Dovid didn’t only see the weaknesses and insecurities in those who were down and out, he saw the holes in the so-called ‘mutzlachim’ also. He knew what we needed to hear and he made sure we heard it. We loved him too.”

The media coverage in the weeks following his passing on 27 Sivan last year at age 77 indicated that others got it too. Every frum newspaper and website seemed to have discovered the magic of this man and his approach, the stories and videos and pictures coming in the kind of deluge usually reserved for a gadol hador.

For half a century, Rabbi Trenk shaped the chinuch landscape at the grass-roots level. He married Rebbetzin Leah (Bagry), and after several years in kollel, he took a position teaching ninth grade in Yeshivas Mir-Brooklyn. In 1971, the Trenks moved to Adelphia, New Jersey. Before there were experts and response teams, Rabbi Trenk was working alongside Rav Yerucham Shain at the Adelphia yeshivah of the 1970s, reaching young bochurim with the searing power of his optimism and faith. For decades he taught in Camp Munk (referring to himself as the oldest camper), and eventually moved from Adelphia to found Yeshiva Moreshes Yehoshua in Lakewood.

So what was it? What’s the Trenk doctrine?

There was a tremendous ayin tovah there, to be sure, a joy in the successes of others, and a gentle, patient, wise, encouraging smile to talmidim, friends, neighbors, acquaintances, and every single Yid.

There was an unusual freshness and energy, a willingness to be human, to be himself. On a rainy summer day in Camp Achim decades ago, Rav Elya Brudny explained it to me by quoting the pasuk in Koheles (7:29): “Asah Elokim es ha’adam yashar — Hashem made man to be straight, v’heimah bikshu cheshbonos rabbim — but they have sought many intrigues.” People make things complicated.

“Who doesn’t want to embrace a talmid who asks a good kushya? Which maggid shiur doesn’t want to break out in a dance when he says over the vort of a Reb Chaim? But we have cheshbonos — this doesn’t past and that will look strange and people will think we’re strange — so we lose the yashrus. But Reb Dovid never did,” Reb Elya said. “He had the purity of a child and never veered from the way Hashem created him. Yashar. Holy. Pure.”

It was this simplicity and clear vision that allowed him not to just see what others missed, but also to miss what others saw. By him, it was an art.

Oops! We could not locate your form.