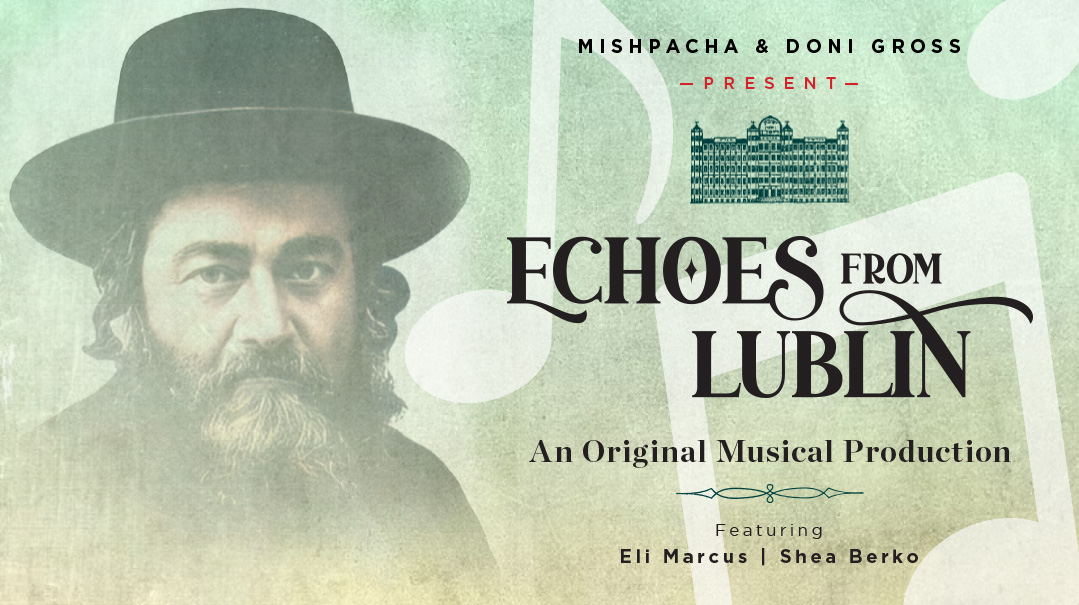

A Light from Lublin: Rav Meir Shapiro’s Quest to Build Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin

Rav Meir Shapiro dreamed of an institution that would change the definition of what a yeshivah could and should be... A century later, the changes he instituted are alive and thriving

With additional research by Moshe Dembitzer

Photos: Kiddush Hashem Archives, Grodzka Gate - NN Theater (Lublin), Yad Vashem, Ghetto Fighters Museum, Rabbi Avraham Frischman, Rabbi Dovid Kamenetsky, DMS Yeshiva Archives, Rabbi Dovid A. Mandelbaum, Walkin Family Machon Meir L'Doros (A. Rotenberg), Piotr Nazaruk, The Museum at Yeshivat Chachmei Lublin, Prof. Moses Schorr Foundation, US Holocaust Museum, Yoeli Hirsch

Rav Meir Shapiro’s name is synonymous with daf yomi, his innovative program for Gemara learning that has Jews across the globe studying the same folio in unison. But he often remarked that he had two “children” — two epic missions that would serve as his eternal imprint in the world. At first glance, it might seem that only the first child — the daf yomi initiative — remains a dominant force in the Torah world. After all, the other child, Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin, was dismantled and most of its students were slaughtered by the Nazis.

But in many ways, Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin still exerts influence. Rav Meir’s vision did not encompass the building alone. Despite doubts, outright opposition, and funding pressures that drove him to penury, he dreamed of an institution that would change the definition of what a yeshivah could and should be, and that would elevate the status of lomdei Torah. A century later, the changes he instituted are alive and thriving.

LISTEN to a selection of Rav Meir Shapiros compositions HERE

January 1927

IN a small town outside Philadelphia, a crowd of Jews gathered at a reception held in honor of a visiting Polish rabbi. They were eager to hear the charismatic orator talk of his groundbreaking initiative to construct a massive five-story building in the heart of the Second Polish Republic. More than a mere building, it would serve as a “Central Yeshivah,” an elite institution that would transform the landscape of Torah study in Eastern Europe.

The chairman commenced his introductory remarks, describing the many accomplishments and talents of the dynamic young rabbi from Poland: just months shy of his fourtieth birthday, he was already serving in his third rabbinic position while simultaneously nearing the end of a five-year term as a delegate to the Polish Sejm. The chairman proceeded to introduce Rav Meir Shapiro as the headmaster of a school serving “hundreds of young Jewish girls.”

“I had the urge to correct the record,” Rav Meir recounted several years later to the journalist David Flinker (1897–1978), “but my companion, familiar with American manners and etiquette, whispered in my ear: ‘One mustn’t ever contradict a chairman. His words are considered sacrosanct.’ Left with no alternative, I waited in silence for my turn to speak.”

Rav Meir rose to address the crowd. Building on a theme from a recent parshah, he told of Pharaoh’s daughter rescuing a baby from the Nile, a child who ultimately blossomed into the savior of the Jewish nation. “The scholars and students of Poland are drowning in the floodwaters of misfortune and poverty!” he told the crowd. “If American Jewry won’t reach out and save them, who can say how many potential leaders will be swept away?”

Stepping down from the podium, Rav Meir was certain his passionate exhortation had made an impact. Then he overheard an exchange between a member of the audience and his young son.

“Dad, did the Poles really try to drown that fellow?” the youngster asked, gesturing in the direction of the speaker.

“You heard him,” affirmed his father.

“And he survived?” the son persisted.

“Well, here he is,” replied the man.

“He’s a good fellow,” declared the boy. “Give him a few dollars.”

Today it’s hard to imagine such a dubious reception for the brilliant and accomplished visionary who founded both daf yomi and Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin. But back when Rav Meir Shapiro shared his pioneering concept of a yeshivah that provided its students with material stability along with true dignity, he encountered significant and sustained opposition. It took years of fundraising, behind-the-scenes lobbying, and the loss of both his personal savings and health to ensure the stability of Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin. But the glorious institution that resulted from his perseverance became much more than a yeshivah. It set new, higher standards for the welfare of its own — and, ultimately, all — yeshivah students, permanently elevating their status amid the communities entrusted with the responsibility for their care.

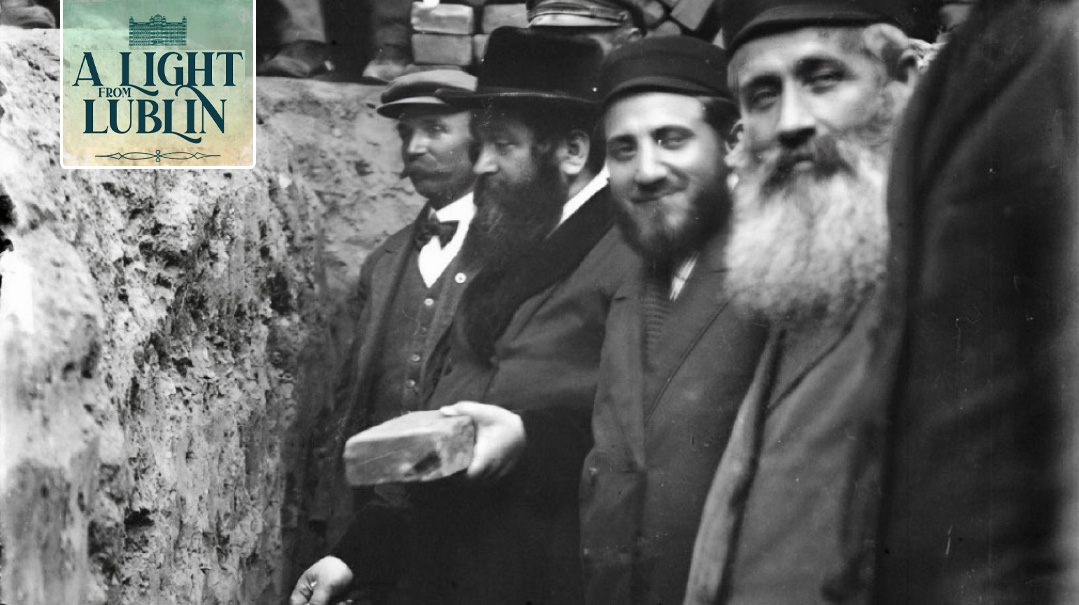

Just a few years earlier, on Lag B’Omer 1924, the old Jewish cemetery of Lublin had pulsated with unusual vitality. A small group of yeshivah students from Piotrkow along with some curious onlookers assembled in the cemetery, their collective gaze fixed upon one magnetic figure.

Amid the ancient gravestones stood the 36-year-old Rav Meir Shapiro, an unusually gifted scholar and rosh yeshivah who had risen to prominence in the preceding years and had recently been appointed rav of Piotrkow. As he faced the gravestones of some of Poland’s greatest Torah scholars, the words he uttered seemed to resonate with the weight of centuries:

“To you great rabbanim, the scholars of Lublin, who spread Torah in this city. You established great yeshivos and nurtured many students… I have come to tell you that I, your servant, Yehuda Meir ben Margala, has decided to restore the crown to its rightful place and I am inviting you to join us in the laying of the cornerstone for this yeshivah, a place where we will raise the honor of Torah until the coming of Mashiach. I am confident that it’s in your merit and in the merit of the Torah that I will succeed in my endeavors for the sake of His great Name and His Torah.”

The cornerstone for the most ambitious yeshivah project of its time was laid later that Lag B’Omer day in front of 50,000 onlookers. The new yeshivah was named Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin, in acknowledgment of the city’s seminal historic role in the blossoming of Torah study in Poland. Lublin had been host to some of the Jewish nation’s most influential disseminators of Torah — including but not limited to Rav Shalom Shachna, the Maharam of Lublin, the Maharshal, as well as chassidic masters such as the Chozeh, Rav Leibele Eiger, and Rav Tzaddok HaKohein — and Rav Meir hoped his new yeshivah would be a fitting addition to the city’s impressive Torah pedigree.

Flanked by rabbinic and chassidic leaders, Rav Meir addressed the groundbreaking ceremony, where he explained that timing the event for Lag B’Omer was hardly coincidental, for Rabi Shimon bar Yochai had been spurred by the same motive. “Chas v’shalom, Torah will never be forgotten,” Rabi Shimon had declared, citing the pasuk, “Ki lo sishakach mipi zaro.”

The continent had recently emerged from the First World War, which had wreaked havoc upon Eastern Europe, uprooting families and entire communities. The region’s yeshivos were victims as well; many had completely disbanded during the war years. When recovery commenced, the rampant hunger, disease, and homelessness took priority over reinstating Jewish education. (At the previous year’s Knessiah Gedolah, Rav Pesach Pruskin (1879–1939) had bemoaned the fact that among Poland’s three million Jews, there were hardly six or seven thousand yeshivah students.) But a select few chose to act on Rav Shimon’s pledge of “Ki lo sishakach mipi zaro,” and invested prodigious efforts to ensure that Eastern Europe’s Torah learning would be restored to its former glory.

Rav Meir Shapiro was one of those select few. What forged his tenacity and vision?

Rav Yaakov Shimshon Shapiro was named after his ancestor, Rav Yaakov Shimshon of Shepetovka, a close student of the Maggid of Mezeritch, and of Rav Pinchas of Koretz

Chapter I: A Class of His Own

Every Precious Day

Rav Yehuda Meir Shapiro was born on March 3, 1887 (7 Adar 5647), in the town of Suceava (Shatz), Romania. His father, Reb Yaakov Shimshon, was a learned chassid and a descendant of Rav Pinchas of Koretz, one of the prime disciples of the Baal Shem Tov. His mother, Margala (Margalit), was the daughter of the gaon of Monistritch, Rav Shmuel Yitzchak Schor, author of the Minchas Shai and a descendant of the author of Tevuas Shor. His ancestry traced back to Rabbeinu Yosef Bechor Shor of Orleans, one of the Baalei Tosafos. Margala Shapiro also carried a maternal connection to the eminent halachic authorities the Bach and Taz.

During his early studies at the local cheder, young Meir faced significant challenges. At the time, these struggles seemed to destine him for a future as a local laborer’s apprentice. He had a form of dyslexia that made the initial steps of reading a formidable task. But he circumvented this challenge with significant exertion and gained an uncanny ability to recognize words in their entirety, sidestepping the conventional method of piecing together individual letters.

An often overlooked factor in Rav Meir’s growth was the unwavering commitment of his mother, Margala, to his Torah learning. When a private melamed they’d hired named Reb Shalom of Sochatchov was late in arriving after Pesach in 1894, Margala’s distress was palpable. “Do you know, my son,” Rav Meir recalled her saying, “that every day that passes without Torah study is an irreplaceable loss. We offered him [what we thought to be] a very handsome salary, but maybe we offered him too small a sum. Torah is so great and priceless; it may have been too small a sacrifice. Who knows?”

(Rav Avrohom Ausband, rosh yeshivah of Telshe Alumni in Riverdale, has theorized that this emphasis on the indispensability of daily Torah study may have been the driving force that later spurred Rav Meir to initiate the daf yomi program.)

This Reb Shalom was the cornerstone of young Meir’s education for six formative years, and his teachings set Meir on a path to greatness. Sadly, Rav Meir Shapiro’s mother passed away during the turbulent years of World War I, never to see her son’s ascent to prominence in the world of Torah. But the memories of her dedication and sacrifices left an indelible mark on him, as this story, shared by one of Rav Meir’s leading students, Rav Yitzchok Dovid Flekser (1917–1999), later one of the roshei yeshivah at Yeshivah Sfas Emes in Yerushalayim, demonstrates:

“Once, when speaking at a large gathering in Poland, Rav Meir suddenly stated with great emotion, ‘Rejoice and be glad, my mother in Gan Eden, be happy, see the stature and respect accorded to your son, who has grown to become one of the gedolei Yisrael!’ The audience was surprised, not knowing why Rav Meir had praised himself in this fashion, but he immediately turned to the women’s section and called out, “And you, women of Israel, worthy mothers, if you want your sons to become great talmidei chachamim and rabbanim, follow the path of my saintly mother, who sacrificed herself in order to dedicate her son to Torah.”

After advancing beyond the local cheder, young Meir was taken under the wing of his maternal grandfather, Rav Shmuel Yitzchak Schor of Monistritch. This would be a foundational phase in his development. Rav Schor nurtured his grandson’s inherent abilities, also introducing him to the multifaceted environment of communal responsibility. In tandem with his meteoric growth in Torah knowledge, the seeds of his legendary leadership skills were sown.

In 1903, his grandfather suddenly fell ill. During his final days, he drew his grandson close and issued final instructions: “Return to your parents in Shatz. The truth is that I believe you really don’t need me anymore. I hope and trust that you will be able to learn and absorb more Torah than I ever could convey to you.” On the 7th of Adar, as “the Illui of Shatz” turned 16, his grandfather passed away, and the budding Torah giant returned to his hometown.

Rebbetzin Malka Toba Shapiro (bottom left) with family members

Saved By the Shatzer

ITwasn’t only local Torah scholars who welcomed the young scholar back to his hometown. Rabbi David Avraham Mandelbaum — who has devoted his life to furthering the legacy of Rav Meir Shapiro and the story of Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin — shared a startling anecdote in his work Igros V’Toldos: Rabbeinu Maharam Shapiro M’Lublin ztz”l.

Upon young Meir’s return to Shatz, enlightened family members attempted to convince him to attend the regional technical school in the Moldavian cultural capital of Jassy (modern-day Iași). Upon hearing of these influences, Rav Shalom Moskowitz, the Shatzer Rav, immediately protested so vociferously that he threatened to lie down in the street and physically obstruct the path of any carriage transporting the town’s prodigy to a secular school.

Rav Meir obeyed the Shatzer Rav and remained under his tutelage. Under the Shatzer’s guidance, he ventured into the esoteric world of Kabbalah, a sphere many deemed too advanced for someone his age. As his understanding and wisdom grew, Meir was empowered to impart knowledge and assisted in laying the foundations of a yeshivah in the quiet town of Shatz, a step that cemented his reputation in the Torah world.

The long list of luminaries who served in the rabbinate in Rav Meir’s hometown of Shatz include Rav Yoel Moskowitz, son-in-law of Rav Meir of Premishlan, his grandson Rav Shalom (the famed Shatzer Rav), Rav Meshulam Roth and Rav Meir’s cousin, Rav Moshe Chaim Lau (pictured here), father of Israel’s former Chief Rabbi Yisrael Meir Lau

One Lag B’omer, when he was a mere 17 years old, Rav Meir amazed Rav Yisrael Hager, the Ahavas Yisrael of Vizhnitz (1860–1936), by delivering an impromptu speech connecting the various statements of Rabi Shimon bar Yochai throughout Shas. Upon meeting him for the first time, Rav Shalom Mordechai Schwadron, the Maharsham (1835–1911), was so impressed that he recited a brachah. Soon enough, an array of renowned Torah scholars ordained him.

Rav Meir’s primary mentor was Rav Yisrael Friedman, the Tchortkover Rebbe (1854–1934). As a Tchortkover chassid (and a lifelong follower of the Rebbe), the Rebbe advised him over the course of his varied roles in communal leadership. Even as Rav Shapiro’s own star ascended, their bond retained its essence: a deep chassid-rebbe connection rooted in mutual respect and reverence for Torah.

In 1907 Rav Meir married Malka Toba, the daughter of Reb Yaakov Dovid Breitman, a prosperous Tarnopol landowner. The young couple shared a mutual vision for Polish Jewry. The financial standing of the Breitman family aided Rav Meir’s ambitions, with Malka Toba staunchly supporting him in each of his endeavors.

Rav Yisrael Hager, the Ahavas Yisrael of Vizhnitz, was amazed by a 17-year-old Rav Meir Shapiro

Educational Architect

The couple initially settled in Tarnopol, where Rav Meir transformed his father-in-law’s home into a hub of Torah study. In 1910, with the encouragement of the Tchortkover Rebbe, Rav Meir was appointed rav of the Galician town of Galina. Writing in the town’s Yizkor book, a former resident, the journalist Asher Korech (1879–1952), describes Rav Meir’s decade-long rabbinic tenure (which was punctuated by several years in Tarnopol and Lemberg during World War I). For several years Rav Meir refused a salary from the town and referred halachic inquiries to two elder dayanim, Rav Yechezkel Hochberg and Rav Dov Goldberg, enabling them to retain their positions.

Korech writes, “Even when the community council persisted in offering him a salary, Rav Shapiro’s innate magnanimity shone through. He chose to distribute the funds among the impoverished yeshivah students and those ardently dedicated to Torah study. His guiding principle was clear: uphold G-d’s glory and put personal pride aside for the greater good.”

When a member of the community complained that at the age of 23, Rav Meir was perhaps too young for such a position, the young rabbi smiled and responded that every day he would do something about it.

The early years of Yeshiva Bnei Torah in Galina. Rav Meir is seen at center

Korech notes the crowning achievement of Rav Meir in Galina was the establishment of Yeshivah Bnei Torah, which changed the town’s spiritual trajectory:

The landscape of Torah study within our city underwent a seismic shift with the arrival of the esteemed Rav Meir Shapiro. His arrival couldn’t have been timelier, as the town had undergone a palpable decline in Torah dedication among its youth."

A majority had transitioned from traditional Torah study halls to the school established by Baron Hirsch. Consequently, these chambers of Torah wisdom, once bustling with spirited debates and fervent study, now echoed with an eerie silence… The community, although deeply distressed by this evolution, felt powerless to reverse the trend.

However, Rav Shapiro perceived this shift not merely as a challenge but with true, heartfelt sorrow. Possessing an unwavering passion for Torah and an indomitable spirit, he sought to rekindle the city’s once-vibrant Torah spirit. As a testament to his dedication, he instituted the “Bnei Torah society.” With an eye toward the future, he repurposed a centrally-located edifice, tailoring it to serve as a Torah institution, replete with sections spacious enough to accommodate a burgeoning student body.

For the youth, he ensured that the finest educators were appointed, implementing a curriculum he envisioned. Initially, he personally supervised the classes, ensuring the highest standards. Later, this mantle of responsibility was passed on to his advanced yeshivah students, who continued his legacy of vigilance, guaranteeing that educators remained devoted and true to their sacred task.

Under his aegis, the institution thrived, marked by exemplary discipline and fairness. Salaries for educators were punctual, freeing struggling parents from any financial concerns. Students were periodically assessed, with report cards detailing their progress, a testament to the structured approach he championed. Economic standing was never a criterion; both affluent and underprivileged were judged solely by their commitment and prowess in Torah, with the latter group being exempt from tuition fees.

Rav Meir realized early on that the quality of the educational institution depended on the quality of the teachers. When speaking of the importance of having excellent, well-paid teachers of Torah he said, “Look at the difference. When a community hires a shochet, they examine him closely to see if he knows all the laws of shechitah and he is a God-fearing man. And what do they entrust to his hands? An animal! And yet, when they must hire a melamed, to whom they entrust the chinuch of the children, they’re not quite so particular!”

In his early twenties, Rav Meir authored his first sefer, a Torah commentary called Imrei Daas, which linked Talmudic passages to the weekly sedra. Tragically, the manuscript was destroyed during the Russian shelling of Tarnopol during World War I. One page of the sefer, which was salvaged from the blaze, was ultimately buried with him. Also surviving were the haskamos written by some of the greatest gedolim of the time, including the great Galician gaon Rav Meir Arik (1855–1925), the Maharsham, and the aforementioned Vizhnitzer Rebbe, who refers to Rav Meir as “a new vessel containing old wine” who was “learned in all areas of Torah study,” and “a reason to rejoice for there were now new gedolim emerging to take the place of the previous generation.”

The Maharshal’s shul in Lublin (1567-1942)

From Lublin Shall Go Forth Torah

IN

choosing the name and venue of his yeshivah, Rav Meir Shapiro was acknowledging Lublin’s prime location on Poland’s Torah map. For centuries, it served as a city of great scholarship and as home to some of history’s preeminent talmidei chachamim.

Poland’s first great yeshivah was founded in Lublin in 1518 by Rav Shalom Shachna (1495–1558), a student of Rav Yaakov Pollack (1465–1541), considered the pioneer of the pilpul methodology of Talmudic study, and one of the early rabbinical leaders in the old Polish kingdom as German Jews migrated east to Poland during the 15th century. Another student of Rav Yaakov Pollack was Rav Meir Katzenellenbogen (Maharam Padua), who emerged as a leader of Italian Jewry.

Rav Shalom Shachna’s students included his future son-in-law, Rav Moshe Isserles (1530–1572), more commonly known as the Rema; Rav Chaim ben Betzalel (1520–1588), elder brother of the Maharal; and Rav Shlomo Luria (1510–1573), the Maharshal. The Maharshal, whose classic works include Yam Shel Shlomo and Chochmas Shlomo, established a yeshivah in Brisk before assuming the rabbinate in Lublin, a role that also included the stewardship of the local yeshivah.

The Lublin yeshivah was the most prominent one in the entire Polish Kingdom, and there the Maharshal nurtured the next generation of Torah scholars, including Rav Shlomo Ephraim Lunshitz (1550–1619), author of the Kli Yakar and rav in Prague; Rav Yehoshua Falk Katz (1555–1614), author of the Derisha/Perisha and Semah; and Rav Mordechai Yaffe (1530– 1612), author of the Levush.

Later Lublin was home to Rav Meir ben Gedalia (1558–1616), the Maharam of Lublin, whose list of students included the Shelah Hakadosh, Rav Yeshaya Horowitz (1558–1630); and Rav Yehoshua Heschel Charif (1580–1648), author of Meginei Shlomo. In the 17th century, Rav Meir Shapiro’s ancestor, the “Rebbe Rav Heshel,” served as rav of Lublin and teacher of Rav Dovid Segal (the Taz) and Rav Shabsai HaKohein (the Shach).

The golden age of Torah in Lublin ended with the Chmielnicki massacres of 1648–1649, known as gezeiros Tach v’Tat for the Hebrew years when the bulk of the destruction occurred. More than a century later, the chassidic movement arrived in Lublin.

The chassidish character of the city was significant to Rav Meir Shapiro, who wished to fuse chassidic values with Torah supremacy. At the turn of the 19th century, one of the most influential tzaddikim in the history of Polish chassidus, Rav Yaakov Yitzchak Horowitz (1745– 1815), the Chozeh of Lublin, established his court in the city. Some 50 years later, Lublin was graced with the founders of the Lublin chassidic dynasty as an offshoot of Ishbitz. Its leaders, Rav Leibel Eiger (1815–1888) and Rav Tzadok HaKohein (1823–1900), originated from non-chassidic backgrounds. The Eiger family continued to lead the city’s chassidic community until its destruction in the Holocaust, with Rav Shlomo Eiger serving for a time in a capacity in Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin.

From 1580–1764, Lublin was the seat of the “Vaad Arba Ha’aratzos” (Council of the Four Lands), the semi-autonomous political-administrative body for the Jews of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and was the site of the first Hebrew printing press in the region during the 16th century. This led to an interesting phenomenon where many yeshivos in the Lublin district studied the same masechta, in order to assist the local publisher in completing the first set of Shas printed in Poland. This practice also proved to be a unifying force among the local yeshivos. Perhaps this tradition further entrenched the concept of daf yomi in Rav Meir’s mind.

In channeling the rich history of Torah learning in Lublin, Rav Meir Shapiro believed that he was not merely building a new yeshivah, but rather reviving the city’s rich heritage. The name Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin was full of meaning, and the revival of the historic period of Torah greatness in Poland, at a time when Torah study and observance were on the decline, was the mission of Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin.

The Rebbe from London

Rav Shalom Moskowitz was born on 17 Kislev 1878 in Vyrbranivka, near Lvov. One of 17 children, his illustrious lineage is traced to Rav Yechiel Michel of Zlotchov, the Zlotchover Maggid (1731–1786), while his grandfather Rav Yoel was the son-in-law of Rav Meir of Premishlan. The family were devoted Belzer chassidim and he was named for the first Belzer Rebbe, the Sar Shalom (1781–1855).

His early Torah education was under the tutelage of Rav Eliyahu Shmuel Schmerling of Babruysk and Rav Shalom Mordechai Schwadron of Brezan (the Maharsham), who deeply influenced Rav Shalom with his clear and decisive halachic rulings. His exposure to the teachings of Kabbalah came through his uncle Rav Leibish Halperin.

Physically Rav Shalom was an imposing figure, tall and regal. His radiant countenance, accentuated by a flowing white beard, commanded respect. His 16-year tenure as rabbi of Shatz ended following a disagreement with community leaders over a local shochet. Refusing to compromise on halachic principles, he left the town, without any idea how and where he would earn a living. Marrying his cousin Shlomtze in 1897, their life journey took them through various European cities, including Tarnow, Cologne, and eventually London, where he resided for the last three decades of his life.

His commitment to Torah study was unparalleled, and he often dedicated 18 exhaustive hours daily to his davening and learning. In the years preceding his passing, despite having suffered the loss of his beloved wife and five adult children, he remained steadfast in his rigorous study routine. With only his daughter Miriam Chaya at his side, he poignantly remarked, “Were it not for the Torah that is my delight, I would have perished in my anguish” (Tehillim 92). A testament to his erudition came from the Chazon Ish, who once remarked, “Der Rebbe fun London kenn lerenen — the London Rav is a scholar.”

Rav Shalom’s quest to master both the hidden and revealed Torah was vast and unique. When he passed away in London in 1958, he was deeply engrossed in the writing of Daas Shalom, a commentary on Chumash arranged according to the order of Perek Shirah. To ensure accuracy and gain a profound understanding of the subject matter, he studied zoology and made regular visits to the London Zoo. He was also interested in astronomy and botany and frequently visited Munich’s Sternwarte Planetarium while residing in Germany. On one occasion he drew the attention of the curator to two errors in the description of the exhibits.

The Shatzer Rav’s legacy remains an inspiration and continues to this day with frequent visits to his gravesite in London. At the Enfield Adath Yisrael cemetery, his ethical will is emblazoned across the wall of the ohel:

It’s well known that I have always tried to help people to repent of their evil ways, and thanks to Hashem I have succeeded many times. Therefore, whoever is in need of any kind of yeshuah (salvation) or refuah (recovery from illness) for himself or for someone else, should come visit my kever, preferably on a Friday before noon, and light a candle for my neshamah and make his request. Let him state his name and his mother’s name. Then I shall certainly intercede with my saintly forefathers that they should awaken G-d’s mercy for a yeshuah or refuah.

But there is a definite condition attached: the person concerned must promise to improve his standard of Yiddishkeit. For example, he whose business is open on Sabbath must promise to keep it closed. He who shaved his beard with a razor blade should now remove it in a way that is permissible. A woman who does not cover her hair must promise from now on to wear a sheitel (wig). All this must be clearly known to those who come to my tomb. They must keep their promise and should not try to deceive me, G-d forbid, for I shall be very angry. Unfortunately, there is already too much deceit in this world.

Oops! We could not locate your form.